|

War has its own language, then makes

its way into modern everyday usage

War affects everything. Even words and language.

Here are eight examples that emerged from the Civil War.

Deadline

In Civil War military prisons, the “dead line” referred to the line drawn around a prison outside of which prisoners were liable to be shot.

In 1920s journalism slang, it became the time by which material had to be ready for inclusion in a particular issue of a publication.

(Hearing it through the) grapevine

In the modern sense, the grapevine refers to the circulation of rumors and unofficial information. It came from the Civil War-era notion of a dispatch by grapevine telegraph, referring to information passed unofficially from person to person rather than through official communication sources such as the telegraph.

Carpetbagger

Following the Union victory, there was a flood of immigrants from the Northern states to the South, some of them hoping to secure political influence in the governmental disarray after the war. Southerners took to calling this group of people “carpetbaggers,” a derogatory term that implied that their property qualification consisted of no more than the contents of the carpet bag they carried. Today, it often refers to an unscrupulous person.

Shoddy

This word was used during the Civil War to refer to those who made vast sums of money – thanks to army contracts – by allegedly producing clothing largely made out of shoddy (shreds of refuse woolen rags) rather than higher quality cloth. Now, shoddy refers to something poorly made or done.

Rebel yell

This is a shout or battle cry used by the Confederates as they went into battle. In modern usage, it still can refer to such a cry or a brand of bourbon whiskey.

Skedaddle

In Civil War military slang, the word meant to retreat or retire hastily or to flee, referring specifically to soldiers or troops. Today, the word generally means to depart quickly or hurriedly run away.

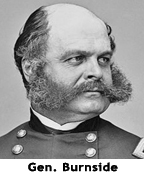

Sideburns Sideburns

Union Gen. Ambrose Burnside (1824–81), later a U.S. senator, is probably best remembered for his distinctive facial hair. However, two major changes happened to the style since the time of Burnside: (1) the mustache disappeared so that the style featured a strip of facial hair extending from the hairline down each side of the face, and (2) the word became plural – sideburns.

Lost cause

The term shot into prominence due to its association with the Confederacy, which sympathizers began to refer to as the “Lost Cause.” Now, it refers generally to a person or thing that can no longer hope to succeed or be changed for the better.

|