|

Confederates in jungle are last survivors

of what South was like during Civil War

By RON SOODALTER

(EDITOR’S NOTE: Ron Soodalter is the author of “Hanging Captain Gordon: The Life and Trial of an American Slave Trader” and a co-author of “The Slave Next Door: Human Trafficking and Slavery in America Today.” He is a frequent contributor to America’s Civil War magazine, and has written several features for Civil War Times and Military History.)

Confederados

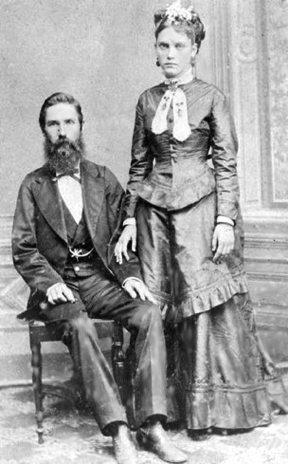

Joseph Whitaker and Isabel Norris were two of the original

U.S. Confederates who migrated to Brazil following the

end of the Civil War. It is estimated that some 40,000

Southerners settled in the South American state of

Sao Paulo rather than face living under Northern rule.

|

This particular Fourth of July setting is in the South – very far south, in Brazil.

The Festa Confederada is held as often as four times a year in Campo, an area carved out of the sugar cane fields outside Americana, a modern city of some 200,000 residents in the state of São Paulo. All the participants are “Confederados” – fifth-generation descendants of Southerners who immigrated here in the days following the Civil War. The entire scene – the dress, the music, food, even the conversation – is a carefully rendered homage to those disaffected rebels who elected to leave their conquered nation and make a new home in a foreign land.

By 1866, the future for countless Southerners appeared bleak. Not only had their bid for nationhood been destroyed; in many instances, so had their homes, their communities and their livelihood. The prospect of living under the harsh fist of the conquering North was more than many were willing to bear. As one Confederado descendant wrote, “Helpless under military occupation and burdened by the psychology of defeat, a sense of guilt, and the economic devastation wrought by the war, many felt they had no choice but to leave.”

There were other reasons. For some, the prospect of laboring alongside former slaves was unacceptable. And then there were those adventurers who hoped to find gold or silver in what was being widely touted as a tropical paradise. Whatever their impetus, for tens of thousands of Southerners, the promise of a new beginning in a new land was irresistible, and Latin America beckoned.

The Southerners’ knowledge of agriculture made them an attractive asset, and a number of countries, including Mexico, Honduras and Venezuela, competed to colonize the disaffected Americans. The most favorable offer, however, came from Brazil’s Emperor Don Pedro II. Desperate to expand the cultivation of cotton in his country, he put together a proposal offering an impressive list of amenities, including the building of a new road and rail infrastructure for conveying crops to market. Brazil had been a strong ally to the Confederacy throughout the war, harboring and supplying rebel ships. And although Brazil had closed its ports to the African slave trade in 1850, it would not abolish slavery for another 38 years. Of all the Latin American nations, Brazil was the one with which the Southerners felt the strongest bond.

In contrast to the often-tired crops of the American South, Brazilian cotton was of a high quality and could be harvested twice a year. Sugar cane, corn, rice, tobacco, bananas and manioc flourished as well, and Southern farmers, as well as doctors, teachers, dentists, merchants, artisans and machinists, envisioned a glowing future. Brazil would become the New South. The all-too-real obstacles – a foreign culture with a difficult language, strong native competition, an often hostile environment, a racially mixed society, a restrictive national religion, homesickness and the loneliness of distance and isolation – factored little in their plans.

There are no accurate records documenting the exact number of émigrés; some historians have placed the figure at around 40,000, from across the former Confederacy, and even loyal border states. It was high enough, however, to necessitate the formation of colonization societies, with agents whose main functions were to gather information on living conditions and financial prospects and to ensure a smooth transition.

For most, the first destination was Brazil’s capital, Rio de Janeiro. The vessels in which they sailed ranged from small packets to large ships, and while some completed the 5,600-mile voyage in an uneventful month, for others the voyage was arduous, and sometimes fatal. The Neptune sank in a storm off the coast of Cuba, taking with it all but 17 passengers. And an outbreak of smallpox on the Margaret claimed the lives of nearly everyone aboard.

When the Southerners disembarked, they were greeted by brass bands, parades and flowery speeches. One former Confederate general recalled, “Balls and parties and serenades were our nightly accompaniment and whether in town or in the country it was one grand unvarying scene of life, love and seductive friendship.”

The emperor greeted many of the new arrivals personally, as the bands played “Dixie.” As he had promised, the new arrivals were given free temporary living quarters in a Rio hotel, and the food and accommodations far exceeded their expectations.

Conditions would never be this elegant again. Dom Pedro’s grand promises of governmental support for the farmers went generally unfulfilled, through no fault of his own. Coincidentally, the year the Civil War ended brought the outbreak of the War of the Triple Alliance, in which Brazil played a major part. The booming economy of the previous decades collapsed, plunging the country into an economic depression. By the time the first Southerners arrived, the emperor was confronting enormous internal issues, and struggling with poor health. The colonists were left to make their own way.

While most members of the Southern professional class settled in the larger cities, such as Rio and São Paulo, the rest chose to literally plant their roots farther down the coast or in the vast, dense interior. Their scattered colonies dotted a 250-square-mile stretch along the country’s east coast, and great distances often separated them. Many of the chosen locations were inhospitable and ill-suited for growing crops. Without the promised road and rail system, crops that did thrive often grew too far from the market. Farms failed, community leaders died and colonies fell apart under power struggles and losing battles with illness and the elements. The few planters who bought slaves and sought to replicate the old antebellum plantation system found only failure.

Some disillusioned colonists returned home; others migrated to the most successful settlement – the Norris Colony, established in 1865 by Col. William Norris. The former Alabama senator had chosen the site carefully, and it soon became the most populous and productive American colony in Brazil, eventually containing some 100 families. And when the railroad finally did come through, the settlers built the beginnings of the nearby market town that survives today as Americana.

Even here, though, life could be brutal. The former rebel Col. Anthony T. Oliver had immigrated among the first settlers, along with his wife, Beatrice, and two teenage daughters. Within the first year, Beatrice died of tuberculosis, followed shortly by both daughters. When locals denied his wife burial in the Catholic graveyard, Oliver donated a section of his land – dubbed “Campo” – for a Protestant cemetery exclusively for the Confederados. Soon, the colonists built a small chapel nearby, which became the center of worship and connection for the transplanted Americans.

Hard though the life could be, many who chose their locations well and put in the work succeeded. Through the use of what the native Brazilians perceived as advanced cultivation methods and tools, the colonists’ crops flourished. In addition to raising native produce, they introduced such homegrown crops as watermelon and pecans. So popular was the “Georgia Rattlesnake” watermelon that by the late 19th century, Confederados were shipping 100 carloads daily from Americana to various parts of Brazil. Within a short time, the displaced rebels established a reputation as hard workers and as diligent and independent citizens.

They did, however, go to great lengths to maintain their own identity. Although subsequent generations intermarried with the Brazilians, they never lost sight of their history and traditions. This was not always viewed in a positive light.

Wrote one former Georgia planter in 1867, “The Anglo-Saxons are completely ignorant of amalgamation of thoughts and religion. Naturally egotistical, they do not admit superiors, nor do they accept customs which are in disagreement with their preformed ideas. They think it is their right to be boss. In my opinion … the Anglo-Saxon and his descendants are birds of prey, and woe to those who get in their way.”

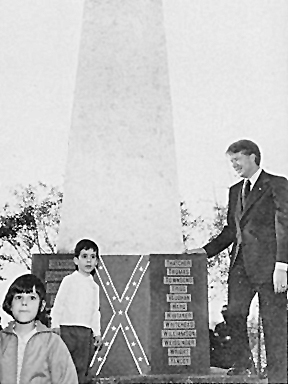

Carter visit

These fifth generation Confederado youngsters posed

with Jimmy Carter during his visit to Brazil in 1972.

They stand at the base of the Confederate monument

near Americana.

|

One clear indicator of the fierceness with which the rebel settlers maintained their identity is in their speech. Despite five generations of assimilation, the English language has survived, perfect and intact, among a number of the bilingual Confederados. Amazingly, although most have not visited the United States, their speech clearly reflects that of the American South. When Jimmy Carter, then the governor of Georgia, visited Campo in 1972, he was stunned: “The most remarkable thing was, when they spoke they sounded just like people in South Georgia.”

The Confederados represent a human treasure trove for modern-day linguists. Throughout the past century and a half, scholars have puzzled over what the Southerners of the Civil War era actually sounded like. The Brazilian descendants’ English, in the words of one latter-day rebel, has been “preserved in aspic”; in its purist form, it stands virtually frozen in time, reflecting the pronunciations and speech patterns of their forebearers, dating from the third quarter of the 19th century.

Similar settlements in Mexico and other Latin American countries faltered; Brazil was the only place where the Confederate émigrés managed to carve a life and an extended community from the jungle, and to found a thriving dynasty. Today, the living descendants of Brazil’s original rebels are scattered throughout the country, and they enjoy the richness of a dual culture. They see themselves as Brazilians, but also as distinctly American – the last rebels of the Civil War.

Says one historian, “They are proud to have Brazil as their mother country, and the United States as their grandmother country.” As one descendant, who learned English before he learned Portuguese, put it, “Actually, we’re the most Southern and the only truly unreconstructed Confederates that there are on Earth. We left right after the war, and we never pledged allegiance to the damn Yankee flag.”

|