|

According to D.F. Faulds…

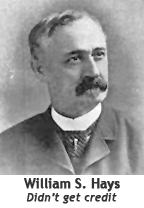

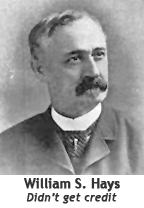

Louisville’s Hays, not Ohio’s Emmett, wrote

lyrics of South’s national anthem, ‘Dixie’

By BRYAN BUSH

Bugle Staff Writer

Who wrote the lyrics to “Dixie?”

Most sources credit Daniel Decatur Emmett, an Ohioan, with developing the words and music of what became known as the Southern National Anthem.

But the message of one of the most distinctively American songs of the 19th century may have derived from Louisvillian William Shakespeare Hays, one of the most famous and prolific songwriters of the 1800s. But the message of one of the most distinctively American songs of the 19th century may have derived from Louisvillian William Shakespeare Hays, one of the most famous and prolific songwriters of the 1800s.

Emmett himself provided confusing accounts of the song’s writing and compounded his authorship by his tardiness in registering the song’s copyright. He supposedly wrote “Dixie” around 1859. But, according to Louisville’s D.F. Faulds, at the time one of the country’s leading music publishers, his employee – W.S. Hays – was the song’s author.

According to Faulds, he said “Dixie” was written in 1857 or 1858. He stated that Charlie Ward entered his office at the age of 15 in 1854 and was a clerk in his publishing company and slept in the music store. Hays also was a clerk in the same company. Both men aided Faulds in the publishing business.

One afternoon in his mail, Faulds received from New Orleans a single sheet of music entitled “Dixie.” When Ward came downstairs the next morning, Faulds gave him the sheet music and asked him to try it on a piano. Faulds stated that the music would make a delightful song.

Hays walked in while Ward was playing the music and Faulds told Hays that he had a new tune and wanted him to write some Southern plantation words for the music. While Ward played the music, Hays began writing words to the melody.

In an hour, Hays wrote four or five verses. By nightfall, Ward had arranged the words and Hays sang it while Ward played the music. In two hours, “Dixie” was written, arranged and sung. Faulds claimed he rushed the song up to the engravers. Shortly after, the song was published by Joe H. McCann, who ran a minstrel show. McCann published the song as “Way Down South in Dixie,” and had 5,000 copies printed and sent all copies to the South. He copyrighted the words, but the music already was common property.

Faulds claimed that Dan Emmett published his version of “Dixie” a year after his publication. Hays version was strictly a Southern version where Emmett’s version was one suitable for singing in the North.

Soon after Emmett’s version of “Dixie” was published, Col. William Pond of the Seventh regiment of New York, stated that Faulds had infringed on his copyright of his song. Pond and Faulds decided to leave their dispute with the Board of Music trade, and, in 1858, the Board met to discuss the copyright issue. Six other instrumental editions of “Dixie” were also brought before the Board, and, with so many versions of the song, the Board decided not to hear the controversy.

Faulds claimed that he had sold 30,000 copies of his song before the Civil War, all in the South, and his version was being sung in the South before Emmitt’s version. Faulds then surrendered his plates to Pond. Pond’s version never was published in the South, but after the war broke out and Louisville being shut off from the South, Faulds version of “Dixie” was copyrighted under the Confederate laws.

The people of the North refused to sing Fauld’s version since the song was considered disloyal. Faulds stated that Pond paid Emmett for his words, while he paid Hays nothing for his version. Pond never reprinted Hays words. He only used Emmett’s words. Unfortunately, the only evidence of this incredible story is Faulds. He claimed in 1894 he lost the only remaining copies of the original version.

During his lifetime, Col. William S. Hays would not only become a famous songwriter, he was a poet, a river editor and a steamboat captain. He was born in Louisville on July 19, 1837, the son of Hugh Hays, a leading pioneer plow and wagon manufacturer in the city. As a youth, young Hays was sent to Mrs. Yubank’s private school, a famous preparatory institution of learning. After finishing Yubank’s School, he attended Hanover College and later Georgetown College in Scott County.

After graduating from Georgetown, he began his career on a steamboat. He was first a clerk and moved up to the position of captain, serving both on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. Before the Civil War broke out, Hays stopped by the Louisville Democrat to see if they would be interested in publishing his articles on riverboat life. John Harney and William Hughes published the Democrat, which later merged with the Courier and Journal.

When Hays walked in, the printing press for the Democrat broke down and the paper was delayed in publishing. Hays stated he could take a look at the press and see what was wrong, since he had learned something about machinery from his father’s factory. Soon, he managed to repair the press and the Democrat hired him on the spot. Hays began publishing his river columns and after the Democrat merged with the Courier-Journal, he continued as “river editor” of the Louisville Courier-Journal. His columns were filled with verse, joke and jingles. While writing for the newspaper, he began to write songs and his songs touched a popular chord both North and South.

During the Civil War, Hays became a war correspondent and also wrote songs such as “The Drummer Boy of Shiloh,” “McClellan is the Man,” “I Am Dying, Mother, Dying,” “Sherman and his Boys” and many others. He was best known for his songs “Evangeline,” “Nora O’Neil,” “Mollie Darling,” “Little Old Cabin in de Lane,” “Keep in de middle ob de Road” and “Old Fashioned Roses are the Sweetest.”

His song “Mollie Darling” sold more than two million copies alone. Amazingly, he sold his music for a sixpence and to minstrel shows.

After the Civil War, during the Reconstruction Period when the country was still torn apart by bitterness towards the South and thousands of Southern families were scattered across the landscape of the country, Hays wrote the “Wandering Refugee.” Another one of his songs that touched on the devastation in the South was “My Sunny Southern Home,” which helped soften and mellow the feeling of the North toward the South.

Controversy arose after the war as to who wrote “Dixie.” Faulds, of course, claimed William Hays wrote the lyrics, and, on May 29, 1898, G. E. Johnson published an article in the Louisville Courier-Journal on the history of “Dixie” and stated why Hays should be attributed to the writing of the song. Johnson claimed that Hays wrote the words to the music composed by Charles Ward and published by Faulds. Johnson stated that Emmett sang the song, making it famous and changed the words to fit his needs.

Regardless of the controversy over who wrote “Dixie,” Hays managed to write 300 songs over his career and sold more than 20 million copies of his sheet music. He became one of the most prolific songwriters in the United States and was one of the greatest patriotic songwriters of the South. When he died in July 1907, newspapers across the United States paid him tribute.

The Baltimore News wrote: “He was one of the most popular songwriters this country has ever produced.”

The Vicksburg Herald wrote: “His fame rested upon his poetic writings of the old river days, and river men and the old South. There is no one else of his ‘quaint individuality’ and the mold of such ‘picturesque’ figures – types of a time that has vanished – is broken. We can no more look for a wearing of his mantle than a return of the old time riverboats and their captains. One would be as much out of place in the activities of life in 1907 as the other.”

William Hays is buried in Cave Hill Cemetery.

|

But the message of one of the most distinctively American songs of the 19th century may have derived from Louisvillian William Shakespeare Hays, one of the most famous and prolific songwriters of the 1800s.

But the message of one of the most distinctively American songs of the 19th century may have derived from Louisvillian William Shakespeare Hays, one of the most famous and prolific songwriters of the 1800s.