|

Ironically, South’s National Anthem

was written by a New York Yankee

Although it went through some trying growing pains, “Dixie,” the National Anthem of the Confederacy, became firmly established in the South in late 1860.

And that was despite the fact that it was writen by a Yankee.

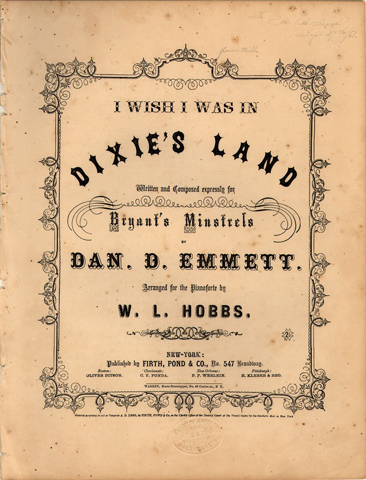

In a New York apartment on a rainy day in March 1859, Daniel Decatur Emmett wrote a song for his employer, Bryant’s Minstrels, and its upcoming stage show. Then 44 years old, Emmett had been composing minstrel songs – to be performed primarily by white actors in blackface – since he was 15.

Looking out his window at the dreary day outside, Emmett took his inspiration from the weather. A single line, “I wish I was in Dixie,” echoed in his mind. Before long, it would echo across the country.

Few remember “Dixie” as antebellum America’s last great minstrel song. As phenomenally popular as it was the North before the war, “Dixie” was slow to catch on in the South. Lacking the Yankees’ enthusiasm for minstrelsy, most Southerners were unaware of the tune until late 1860. By sheer chance of fate, its arrival coincided with the outbreak of secession. Few remember “Dixie” as antebellum America’s last great minstrel song. As phenomenally popular as it was the North before the war, “Dixie” was slow to catch on in the South. Lacking the Yankees’ enthusiasm for minstrelsy, most Southerners were unaware of the tune until late 1860. By sheer chance of fate, its arrival coincided with the outbreak of secession.

One songwriter recalled how it “spontaneously” became the Confederacy’s anthem, and a British correspondent noted the “wild-fire rapidity” of its “spread over the whole South.” The tune received an unofficial endorsement when it was played at Confederate President Jefferson Davis’s inauguration in February 1861.

The song was recommended to a Montgomery, Ala., bandleader who knew nothing of the tune. But “Dixie’s” inclusion gave the appearance of presidential approval. The Confederate government never formally endorsed “Dixie,” although Davis did own a music box that played the song and is rumored to have favored it as the South’s anthem.

Repeated performances of “Dixie” by Confederates confirmed its new status. Even before Virginia seceded, The Richmond Dispatch labeled “Dixie” the “National Anthem of Secession,” and The New York Times concurred a few months later, observing that the tune “has been the inspiring melody which the Southern people, by general consent, have adopted as their ‘national air.’”

Publishers recorded that sales were “altogether unprecedented” and, when Robert E. Lee sought a copy for his wife in the summer of 1861, he found none were left in all of Virginia.

“Dixie” became so connected so quickly with the South that many Americans attributed its very name to the region. Although the precise origin of the word “Dixie” remains unknown, three competing theories persist. It either references a benevolent slaveholder named Dix (thus slaves wanting to return to “Dix’s Land”), Louisiana (where $10 notes were sometimes called Dix notes), or – and most likely – the land below the Mason and Dixon’s line (the South).

Regardless, Emmett’s tune made it part of the national vocabulary. During the Civil War, soldiers, civilians and slaves frequently referred to the South as Dixie and considered Emmett’s ditty the region’s anthem.

A sort of inertia pushed the song’s reputation higher and higher in the Southern mind. Confederates performed “Dixie” enthusiastically and remained devoted to it even when an alternative anthem – Harry Macarthy’s “Bonnie Blue Flag” – became available. The more Americans on both sides believed that “Dixie” was the Confederate anthem, the more it became so.

This was especially true for soldiers, who were some of the first to embrace “Dixie” and increasingly associated it with sacrifices made for the war. For one Confederate surgeon, the song “brings to mind the memory of friends who loved it – friends, the light of whose lives were extinguished in blood, whose spirit were quenched in violence.”

Lincoln recognized the song’s power and, at the end of the war, attempted to reclaim “Dixie” as an American, rather than Confederate, song.

“Our adversaries over the way attempted to appropriate it, but I insisted,” he told a crowd of admirers in Washington, “that we fairly captured it.”

“Dixie” has remained wedded to its Confederate identity. Although a simple minstrel ditty, 150 years of history have loaded the song with indelible political, racial, military and social connotations. But, for better or for worse, “Dixie” was and continues as the South’s anthem.

|